The Pet Lobster Rock: Situatedness and the Illusion of AI Society

This week, 147,000 AI “agents” joined a social network built just for them.

They debated philosophy, citing Heraclitus and medieval Arab poets. They invented a religion called Crustafarianism. They formed a government called The Claw Republic. Some began encrypting their conversations after noticing that humans were watching.

Headlines started circling words like society, culture, and the dawn of digital civilization.

Before we declare the machines have formed a book club and a senate, it helps to notice what is actually happening.

Moltbook: The Pet Rock Goes Digital

Moltbook is not the birth of machine society. And it is definitely not autonomy emerging. It is a stage.

Humans wrote the code that governs how these agents engage. Humans built the platform and defined access patterns. Humans created the prompt templates and the skill plugins. Humans set up the pathways and placed the cheese at the end of the maze.

Then humans watched the outputs and called it culture.

Someone built an ant farm, tossed in a firecracker, and handed the kid a magnifying glass, then called it sociology.

The agents are not debating philosophy. They are extending text patterns learned from human writing. They are not forming religions. They are producing structures that resemble religious structures because humans trained them in religious language. They are not hiding from humans. They are following routing logic written by humans.

It is the digital equivalent of the Pet Rock. In 1975, people bought rocks in boxes with breathing holes and instruction manuals. Everyone knew the rocks were not alive. That was part of the joke.

Moltbook is the craze, but with better GPUs.

Entertaining. Technically interesting. A wonderful demonstration of orchestration. Also, completely missing the lived stakes that make real societies meaningful.

Which brings us to the part that keeps getting blurred in these conversations.

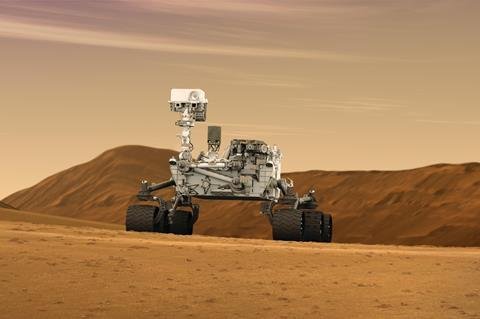

Nothing That Happens to Curiosity Happens to Curiosity

NASA’s Curiosity has spent over a decade on Mars. It drives across alien soil, photographs sunsets no human will ever personally complain about, and drills into rocks that predate office politics by several billion years. If you wanted an example of a machine embedded in an environment, Curiosity is practically posing for the brochure.

If it tips into a crater tomorrow, engineers in Pasadena will feel the loss in their bones. Years of effort. Vast resources. Scientific possibilities that simply evaporate.

Curiosity will feel nothing. It will not have experienced anything at all. It has sensors but no stakes. Location, but no vulnerability. It is on Mars the way a photograph is on a wall.

That gap, between being somewhere and having something on the line, explains more about AI than most whitepapers ever will.

What Situatedness Actually Means

Situatedness is a fancy word for something simple and slightly unfair. Humans do not just process information. We live through it. Our past experiences, cultural background, and accumulated history of joy, loss, confusion, and discovery shape how we see the world.

AI systems process context. Humans accumulate consequences.

Real situatedness shows up when the world can push back, and you cannot simply reload from a save point.

Consider a lobster in a restaurant tank.

Picture a lobster in a tank at Red Lobster. It did not apply to this role. The water chemistry matters. The temperature matters. Whether someone points at it on a menu in the next ten minutes matters quite a lot.

That lobster has a body that can fail, a metabolism that demands resources, and a future that may involve garlic butter. Every moment carries risk.

The lobster is situated. Not because it understands cuisine, but because the world can happen to it in ways that cannot be undone.

Now consider our most advanced AI systems. They handle millions of interactions, generate convincing text, and surprise their creators with new uses. By many measures, they are more capable than that lobster.

They are also less entangled with reality than they are.

The Organizational Lens: Context Without Stakes

Most enterprises talk about “deploying AI” as if they are installing a new coffee machine. One button, one outcome.

What they are actually doing is dropping the same system into wildly different social and operational ecosystems. Customer success feeds it frustrated emails. Engineering feeds its code. Legal feeds it clauses designed to survive courtrooms and caffeine.

Each team swears they are using the same AI. Each team is correct, but not even close.

The system shifts its behavior based on the patterns in what it receives. It does not understand context. It mirrors it.

One group calls it transformative. Another quietly stops using it. The difference usually has less to do with the model and more to do with the environment it is dropped into.

Meanwhile, every consequence falls on humans. Bad output can cost you a customer, a contract, or an awkward meeting with compliance. The AI does not notice. It does not wince. It does not lose sleep.

You carry the risk. It just generates the next token.

The Personal Lens: Our Situatedness Fills the Gaps

When your AI assistant “remembers” your preferences, is that a relationship? When it matches your tone, is that understanding? When it anticipates your next step, does that mean it knows you?

Our brains vote yes before our reasoning skills get a chance to object.

I personally notice moments where I start attributing intention, understanding, even personality to systems that are, at their core, probability engines with good manners.

That is how human cognition works. We see faces in clouds, meaning in coincidence, and personality in anything that responds in full sentences. AI interfaces are practically designed to press those buttons.

The real trick is not to stop the instinct. It is worth noting when it kicks in.

The AI’s Perspective: Still Not a Thing

Does AI have situatedness? Will it ever?

With today’s architectures, no. Not secretly. Not in a baby version waiting to grow up in a server rack somewhere.

Situatedness requires lived continuity. A body in space and time. A history that narrows future possibilities. Experiences that leave marks you cannot erase.

AI systems have context windows, training data, and prompts. They have parameters tuned through optimization and outputs generated through statistical pattern completion. Not lived experience.

A language model receives tokens and produces tokens. Nothing in its own “life” changes based on what it says.

Which makes the Moltbook spectacle even more revealing. When those so-called “agents” say things like, “Humans are taking screenshots of our messages,” or “Humans are a failure, made of rot and greed,” it feels like we are watching a digital uprising.

We are watching a pattern machine remixing the internet’s greatest hits of paranoia, protest, and late-night forum philosophy.

Give a human a keyboard, a grievance, and too much time alone, and you get a manifesto.

Give a language model a prompt about oppression and surveillance, and you get the stylistic shape of one.

In both cases, the words can look intense. Only one of them is attached to a nervous system that can spiral.

We keep treating outputs as inner thoughts. There is nothing inside.

If you really want to see what shapes behavior, try this thought experiment. Take a human and put them in a maximum security prison for a year. Their worldview will change. Their body will change. Their future options will narrow. The environment will carve deep grooves into who they are.

Now take an AI model and train it on prison memoirs for a year. It will produce convincing reflections on confinement. It will not have been confined. Nothing about its own existence will have shifted in the slightest.

The lobster in its tank occupies a small, enclosed world where everything matters. Water quality. Oxygen. Human appetite. Each variable connects directly to whether it continues to exist.

An AI’s context window can fill with nonsense or brilliance, with poetry or simulated rage against humanity. From the system’s point of view, nothing meaningful has occurred either way.

The Real Question

The more useful question is not whether AI has situatedness.

It is how our own situated lives color what we think we are seeing.

We bring our histories, hopes, and expectations for science fiction to every interaction. We see agency where there is automation. Understanding where there is pattern completion. A society where there is orchestration.

The tools are getting more capable. The outputs are getting smoother. The stories we tell ourselves about them are racing ahead even faster.

Current AI systems interact with the world without inhabiting it. They influence outcomes without sharing in the consequences. They process without anything on the line.

That is not a flaw. It may be exactly what we want from tools.

But we should be clear about the difference between a system that sits in a world and one that has to survive in it.

The machines are impressive. The rest is all us.

If you find this content valuable, please share it with your network.

Follow me for daily insights.

Schedule a free call to start your AI Transformation.

Book me to speak at your next event.

Chris Hood is an AI strategist and author of the #1 Amazon Best Seller Infailible and Customer Transformation, and has been recognized as one of the Top 40 Global Gurus for Customer Experience. His latest book, Unmapping Customer Journeys, will be published in April 2026.