Simonomy: Recalibrating the Language of Autonomy in AI

“Autonomous” now labels a wide range of AI systems, from chatbots to recommendation engines. Tension between linguistic accuracy and marketing appeal has stretched the word beyond recognition. Like model drift, the definition has wandered so far from its starting point that it no longer reflects the original concept.

Autonomy originates from the Greek autos (self) and nomos (law), denoting self-governance and the capacity to generate internal rules, purposes, and constraints. All systems today function within externally imposed boundaries, pursue predetermined objectives, and cease operation when deactivated. They lack the ability to modify their own training or govern themselves beyond their programming. This constitutes advanced automation rather than genuine self-governance.

The industry now defines “autonomous” as “operating without continuous human intervention,” a standard so broad that it includes basic devices like thermostats and vending machines. Most people, when using ‘autonomous’ to describe something, define it as purely ‘automation.’

This led me to develop the Autonomy Threshold Theorem to assess genuine autonomous operation. The results are clear: no current system meets this threshold. Despite this, the term ‘autonomous’ remains widely misused.

The Challenge

In a recent post, Stefan Auerbach responded to his experience. Stefan and I have had lengthy conversations about the problem with autonomy. But in this response, he said:

“When I use the alternative and Chris, you know this well, I get beat up for it. I can’t even say the word Heteronomous. Right or wrong marketing already damaged this. There has to be a better alternative.”

He went on to say:

“Let’s market a better-sounding term.”

I contend that autonomy and heteronomy are the most appropriate terms. They are philosophically precise, historically grounded, and convey their intended meanings accurately.

However, Stefan’s challenge cannot be discounted. Autonomy and heteronomy may be the right words, but reclaiming them now would be like trying to convince the world that water is not water, but is extremely temperamental air.

Either way, I can never pass up an opportunity to wordsmith alternatives.

So…

Introducing Simonomy

There is a clear need for terminology that accurately represents these systems’ capabilities, rather than relying on aspirational or marketing-driven deception.

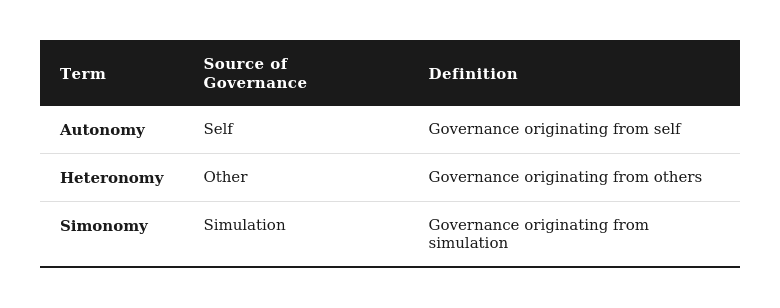

Linguistics gives us two sources of governance.

- Autonomy: governance originating from self.

- Heteronomy: governance originating from others.

But neither term accurately describes what current AI systems actually do. These systems are not governing themselves, nor are they simply being governed by external command in the traditional sense. They are doing something distinct: generating governance-like behaviors through simulation.

This requires a third category.

I propose the term: simonomy.

Where auto + nomos means self-law, and hetero + nomos means other-law, sim + nomos means simulation-law: governance originating from simulation.

Simonomy is the condition in which a system exhibits governance behaviors generated through simulation mechanisms. Pattern inference, statistical modeling, and delegated execution produce the functional appearance of self-directed operation without the origination of purpose, evaluative criteria, or constraint.

A simonomous system is not “failing to be autonomous.” It is not “almost autonomous.” It is doing something categorically different: producing governance-like outputs through simulation rather than through either self-determination or direct external control. Simonomy is its own category, a peer to autonomy and heteronomy, not subordinate to either.

The “sim-” prefix is widely recognized. SimCity is understood as a simulation of city management. Flight simulators are known for modeling flight without actual flight. Simonomy follows this logic, but it does not merely model autonomy as a flight simulator models flight. It describes a distinct source of apparent governance: simulation mechanisms that produce behaviors resembling self-direction without any self-direction actually occurring.

This terminology provides a vocabulary that accurately reflects the current state of technology:

Autonomy should be reserved for systems that genuinely govern themselves, establish their own purposes, adjust their own constraints, and persist without external control. This remains a theoretical objective. The Autonomy Threshold Theorem provides criteria for evaluation, and to date, no system has qualified.

Simonomy describes the current state with precision: systems whose governance behaviors emerge from simulation mechanisms. These systems appear to make decisions and act independently. The simulation is compelling enough that users and marketers routinely conflate performance with genuine self-governance. But the source of the behavior is simulation, not self-determination.

A simonomous system is neither defective nor inferior; it is simply described with greater precision. In an industry saturated with exaggerated claims, such precision is valuable.

A Note on Heteronomy

Kant already gave us a word for what is actually happening in systems. Heteronomy. Governance by external law rather than self-law. Every AI system today is, technically, heteronomous. They operate under rules imposed from outside, by humans, by training, by design.

As I stated earlier, heteronomy is the more precise structural term, offering philosophical rigor and historical grounding. However, I recognize the practical limitations. Expecting the industry to adopt “heteronomous AI” is unrealistic, as the term is academic and obscure, with little market appeal. Vendors are unlikely to describe their products as “heteronomous” while competitors continue to promote “autonomous” solutions.

But simonomy is not simply a more marketable synonym for heteronomy. The two terms describe different things. Heteronomy identifies the structural condition: these systems are externally governed. Simonomy identifies the observable mechanism: these systems generate governance behaviors through simulation. A system can be structurally heteronomous while being operationally simonomous, governed from outside while producing behaviors that appear to come from within. Both descriptions are accurate. They operate at different levels of analysis.

Although I may philosophically prefer heteronomy for structural precision, from a strategic perspective, simonomy is more likely to shape industry discourse, and it captures something heteronomy does not.

Everything is Simulation

A broader reframing is required: AI should be understood not as artificial intelligence, but as an artificial simulation of intelligence.

It is essential to examine the actual functions of these systems. They lack genuine understanding; instead, they simulate it by matching patterns across extensive datasets. They do not engage in reasoning; instead, they simulate it through statistical inference. They do not make decisions; instead, they simulate decision-making using probability distributions. Although the outcomes may appear convincing and often lead observers to believe genuine cognitive processes are at work, the underlying mechanisms differ fundamentally from those of authentic cognition, reasoning, and autonomy.

This observation is not intended as criticism. Simulations are highly valuable. A flight simulator need not achieve actual flight to train pilots effectively, and SimCity does not need to be a real city to teach urban planning principles. The value of simulation lies in its capacity to model phenomena without embodying them.

Problems arise when the distinction between simulation and reality is ignored. Confusing the model with the entity it represents can result in misplaced trust, inappropriate assignment of responsibility, and misguided decision-making.

Simonomy is not an exception; it exemplifies a broader industry trend of systematically conflating simulation with reality. But unlike “simulated intelligence” or “simulated reasoning,” simonomy identifies a specific mechanism, governance behaviors generated through simulation, and gives it a name that stands on its own.

Why This Matters

The language used directly shapes decision-making. When organizations believe they are deploying “autonomous” systems, they often make assumptions about capability, reliability, and oversight that do not correspond to actual system performance.

Governance failures: If a system is truly autonomous, it may warrant distinct legal considerations, such as agency, responsibility, or even rights. If it is simonomous, its governance behaviors are generated through simulation, and full responsibility for its outputs rests with the human operators. This distinction is critical for regulation, liability, and accountability.

Investment distortions: Substantial financial resources are allocated to “autonomous AI” based on promises that current technology cannot fulfill. Investors and executives make decisions based on nonexistent capabilities, expecting self-governing systems while actually acquiring sophisticated simulations.

Trust miscalibration: Users who believe they are interacting with an autonomous agent may extend trust beyond what is justified by the system’s actual capabilities. This can lead to excessive information sharing, unwarranted deference, and insufficient verification. The simonomy framework helps calibrate expectations: the system convincingly produces governance behaviors through simulation, but remains a simulation.

Strategic misdirection: Organizations pursuing “autonomous AI” may neglect the essential task of designing effective human-AI collaboration. Because AI systems are not genuinely autonomous, the human role remains central. Overlooking this reality can result in insufficient investment in the human factors critical to success.

Simonomy and Nomotic AI

This terminology aligns with Nomotic AI, developed as a governance companion to “agentic AI.” Nomotic, derived from the Greek nomos for law, emphasizes governance: AI systems that operate under structured rules, constraints, and accountability mechanisms.

Simonomous systems require nomotic governance precisely because they lack autonomy. Since these systems cannot govern themselves, since their governance behaviors are simulated rather than genuine, external governance is essential. This pairing is logical: simonomous capabilities are developed and embedded within nomotic structures, where simulation-generated behaviors are complemented by genuine human oversight.

This approach avoids attributing capabilities to technology that it does not possess and preserves human responsibility rather than deferring to simulations. It acknowledges that these systems are powerful simulations operating within human-defined constraints and require appropriate governance.

A Challenge

If resources permitted, I would establish a prize of ten million dollars for the first system to demonstrably satisfy the Autonomy Threshold Theorem. This would not reward systems that merely operate independently for a limited period or produce impressive outputs, but rather those exhibiting genuine autonomy: the capacity to self-generate purposes, self-modify constraints, and persist independently of external instantiation.

The prize would likely remain unclaimed for decades; however, the challenge itself would stimulate critical discourse. It would highlight the gap between marketing claims and technical reality, offering journalists, regulators, and buyers a framework for informed skepticism.

In the interim, language remains our primary tool. We can either perpetuate confusion or strive for clarity. Continuing to label every chatbot as “autonomous” risks rendering the term meaningless, while insisting on precision preserves its significance.

I also recognize the deeper challenge here. We are not simply asking people to stop using a word. We are asking them to reconsider what they believe the word means. Most people in the AI industry do not associate autonomy with governance at all. They associate it with capability. With a system that can do things on its own. The idea that autonomy is fundamentally about self-law, about the origination of purpose and constraint, is foreign to an industry that has redefined the word around operational independence. Introducing simonomy is not just a vocabulary swap. It requires people to accept that the concept they have been calling autonomy was never about what they thought it was about. That is a harder ask than coining a new term.

Three sources of governance. Self. Other. Simulation.

These systems are simonomous. They produce governance behaviors through simulation, not through self-determination. Until a system genuinely crosses the autonomy threshold, intellectual honesty requires that we acknowledge this distinction.

A new word exists. Now use it.

If you find this content valuable, please share it with your network.

Follow me for daily insights.

Schedule a free call to start your AI Transformation.

Book me to speak at your next event.

Chris Hood is an AI strategist and author of the #1 Amazon Best Seller Infailible and Customer Transformation, and has been recognized as one of the Top 40 Global Gurus for Customer Experience. His latest book, Unmapping Customer Journeys, will be published in 2026.