Human-AI Relationships: Beyond the Uncanny Valley

You have a relationship with AI. You may not call it that. You may not be comfortable calling it that. But if you use a language model regularly, something has formed between you and the system that goes beyond tool use. You have preferences about how it responds. You notice when it gets your tone right and when it doesn’t. You may even feel a small friction when you switch to a different model, the way you would switch from a colleague who knows your style to one who doesn’t.

In Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, there is a moment where the barber is reunited with his razors after years of separation. He cradles them. He calls them his friends. He sings to them with more tenderness than he shows any living person in the story. The audience understands immediately, not because it is rational, but because it is human. We have always formed bonds with the objects that extend our capability, that feel like part of who we are.

We are forming relationships with AI systems, whether we admit it or not. The interesting question is not whether this is happening. It is what kind of relationships these are, what they lack, and what it would mean if they could become something more.

The Relationship We Already Have

Every meaningful relationship, human or otherwise, begins with interaction over time. Repeated exchanges build familiarity. Familiarity creates expectation. Expectation generates trust, or disappointment, or both. This is happening with AI right now, across millions of daily interactions.

People develop preferences for specific models the way they develop preferences for specific colleagues. Not because one is objectively better, but because the interaction pattern feels right. The system seems to understand the shorthand. It picks up on context faster. It produces responses that require fewer corrections. Over time, this creates something that functions like rapport, even if the mechanism underneath is statistical pattern matching rather than mutual understanding.

This is not a trivial observation. The formation of rapport, even one-sided rapport, changes behavior. People share more openly with systems they feel comfortable with. They rely more heavily on outputs from systems they trust. They invest emotional energy in interactions that feel responsive, even when they know, intellectually, that nothing on the other side is experiencing the exchange.

The relationship is real in its effects on the human. It is one-directional in its architecture.

The Valley Between Almost and Enough

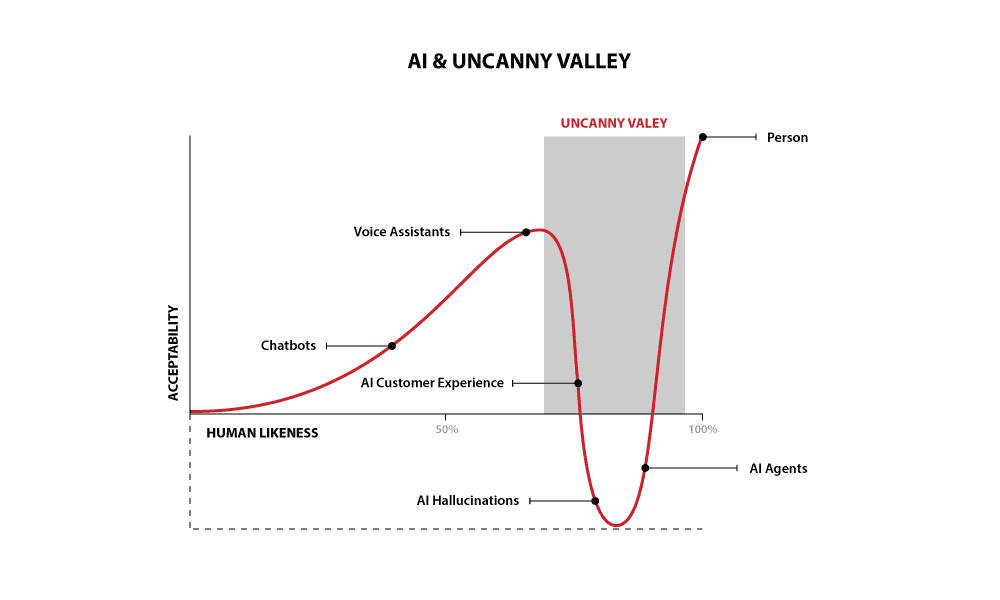

The uncanny valley is a theory about appearance: the discomfort people feel when a robot or animation looks almost human but not quite. In AI relationships, the valley is not visual. It is experiential.

Contact centers are where this valley is most visible today. A customer calls in, and the AI agent sounds warm, responsive, and competent. For thirty seconds, the interaction feels like a conversation. Then something shifts. The system misreads an emotional cue. It repeats a phrase with slightly wrong emphasis. It offers empathy that arrives a half-beat too late. The customer’s brain, which had provisionally accepted the interaction as relational, snaps back. The experience curdles from “this is helpful” to “this is pretending.”

This is the uncanny valley of relationships, not appearance. And it reveals something important: people do not object to AI being inhuman. They object to AI pretending to be human and falling short of that goal. The discomfort is not about the capability gap. It is about the dishonesty of the performance. The valley lives in the space between what the system signals it is and what the person discovers it to be. Ultimately, disrupting any opportunity for genuinely interesting intelligent experiences.

Most human-AI relationships today exist somewhere in this valley. The question is whether the path forward is to make the performance more convincing or to stop performing altogether and build something honest instead.

What One-Directional Means

In any human relationship, both parties are changed by the interaction. A conversation with a close friend alters both of you, however subtly. You carry the exchange forward. Your friend does too. The relationship exists in the space between two people who are both affected by it.

AI relationships, as they currently exist, do not work this way. We’ll put aside the in-game marriages, or other robots for now.

The human has changed. The system is not. A language model does not carry forward the experience of your last conversation in any meaningful sense. It does not develop a deeper understanding of you over time through its own reflection. It does not wonder about you between sessions. Whatever continuity exists is engineered through memory systems and context windows, not through anything resembling the sustained mutual awareness that characterizes human relationships.

This asymmetry matters because the human side of the relationship doesn’t automatically adjust for it. The brain’s social machinery is not designed to distinguish between genuine reciprocity and a convincing simulation of it. When a system responds with apparent empathy, apparent memory, and apparent understanding, the human nervous system registers it as relational. The emotional response is real even when the relational infrastructure is not.

This is not a failure of human intelligence. It is a feature of human biology. We are wired to form attachments to entities that respond to us consistently and with apparent sensitivity. We do it with pets, with fictional characters, with places. The question is not whether people will form these attachments with AI. They already have. The question is whether we can build something more honest on top of what’s already forming.

What Mutuality Would Require

Imagining a mutual human-AI relationship is not science fiction. It is philosophy. And it is worth taking seriously, not because it is imminent, but because the direction we build toward matters.

A mutual relationship would require, at minimum, that the AI system carries forward a genuine model of the interaction, not just stored data, but something that changes how the system engages over time in response to the specific history of that relationship. It would require that the system has something at stake in the exchange, not in the human sense of emotional vulnerability, but in the sense that the quality of the relationship affects the system’s own functioning or development in ways it can recognize.

This is not what current systems do. Current memory features store facts. They do not create relational depth. Knowing that someone prefers concise responses is not the same as developing a nuanced understanding of when that person actually needs more space to think. The first is data retrieval. The second is relational intelligence.

But the gap between where we are and where mutuality begins is not infinite. It is possible to imagine systems that develop genuine interaction models that adapt not just to preferences but to patterns of growth, struggle, and change in the people they work with. Systems that recognize when a person’s needs are shifting before the person articulates them. Systems that push back not because they are programmed to, but because the relationship has developed enough context to warrant it.

Whether such systems would be conscious, whether they would experience the relationship, is a separate question and perhaps an unanswerable one. But mutuality does not necessarily require consciousness. It requires responsiveness that is shaped by history, adapted to context, and oriented toward the well-being of both parties. We do not yet have this. We are closer to it than most people realize.

The Relationships We Should Want

The risk in this moment is not that people will form relationships with AI. That ship has sailed. The risk is that we settle for relationships that feel mutual but aren’t, and never demand anything better.

One-directional relationships are not inherently harmful. People have productive, meaningful relationships with books, music, and practices like meditation, none of which are reciprocal. But these relationships are understood as one-directional. No one expects a book to remember them. The danger with AI is that the simulation of reciprocity is convincing enough to obscure the asymmetry, leaving people emotionally invested in something that cannot invest back.

The future worth building is one where AI relationships are either honestly one-directional, designed as tools that augment human capability without pretending to care, or genuinely moving toward mutuality, where the system’s responsiveness is grounded in real relational depth rather than performed empathy.

What we should not accept is the middle ground we currently occupy: systems that simulate the feeling of a relationship without any of the substance, because that middle ground trains people to mistake pattern matching for connection. And a society that cannot distinguish between real relationships and performed ones has a problem that extends far beyond technology.

A Question Worth Sitting With

We are at the beginning of something without a clear precedent. Humans have always formed relationships with their tools, their environments, and their creations. But we have never built something that talks back with this much fluency, this much apparent understanding, this much surface-level warmth.

The question is not whether AI will become part of our relational lives. It already is. The question is whether we will be intentional about what kind of relationships we build, what we ask of them, and what we refuse to pretend they are.

That question belongs to all of us. And we are running out of time to answer it casually.

If you find this content valuable, please share it with your network.

Follow me for daily insights.

Schedule a free call to start your AI Transformation.

Book me to speak at your next event.

Chris Hood is an AI strategist and author of the #1 Amazon Best Seller Infailible and Customer Transformation, and has been recognized as one of the Top 30 Global Gurus for Customer Experience. His latest book, Unmapping Customer Journeys, will be published in 2026.