The Superman Robots: Why AI May Never Be Autonomous

I recently watched an advanced screening of Superman (2025), written and directed by James Gunn, starring David Corenswet as Clark Kent/Superman. As a quick review, I loved the movie, and I assure you this article contains no spoilers. But it got me thinking deeper about AI Autonomy.

Autonomy remains one of the most frequently misused terms in the field of AI. We apply it to any machine that moves without our constant supervision, as if complexity were the same as choice. Somewhere along the way, we have confused automation with autonomy, inflated the capabilities of machines, and distorted the meaning of the word.

Science fiction didn’t start this confusion, but it often mirrors it. The stories we tell about intelligent machines reflect what we hope for, fear, and are willing to accept as accurate.

A scene in the 2025 Superman film captures the heart of this conversation with clarity.

The Automaton’s Confession

Krypto, Superman’s loyal companion, drags a wounded Superman into the Fortress of Solitude. Bloodied and in extreme pain, he lies on the icy floor as four humanoid machines rush to his aid. Superman looks up, weak but grateful, and says, “Thank you.”

One of the robots replies without pause:

“No need to thank us, sir, as we will not appreciate it. We have no consciousness whatsoever. Merely automatons here to serve.”

The line lands like a thesis statement. The script could have chosen terms like Kryptonian AI or autonomous assistants, especially in today’s marketplace where everyone is overhyped on artificial terminology. But it didn’t. It used automatons. That choice resurrects a word with weight, a term that forces us to confront a distinction we’ve grown too comfortable ignoring.

The word automaton comes from the Greek automatos, meaning “acting of itself,” for distinction, as opposed to “acting FOR itself.” The word first appeared in Homer’s Iliad, where it describes an automatic gate opening. In later centuries, the word described mechanical creations that moved in lifelike ways, for example, 19th-century musical dolls, cuckoo clocks, and clockwork figures designed to imitate life without understanding it.

An automaton moves, reacts, and simulates choice, but it does not choose itself.

This brings us to three questions that define the AI autonomy debate:

- Can autonomy exist without consciousness?

- Can moral reasoning be programmed without sentience?

- Can human characteristics like empathy be excluded from genuine independence?

The Superman scene offers a glimpse into what is often misunderstood. The robots act with precision, coordinate tasks, respond to real-time data, and perform complex procedures with mechanical elegance. But when Superman thanks them, one answers with a line that feels both comical and cold.

They serve, they execute, and they do not appreciate thanks because they lack the humility to receive it.

At that moment, the line between intelligence and AI autonomy becomes visible. More importantly, it becomes undeniable.

Capability Without Understanding

Without empathy, there is no awareness of others. It’s only execution, carried out without emotional consequence. They can perform surgery, pilot a starship, and recite every medical protocol in Kryptonian history. However, they cannot reflect on why those actions matter or ask whether they should act. They follow instructions, however advanced, written and authored by someone else.

This limitation becomes clearer later in the film. When Superman discovers that Krypto has wreaked havoc in the Fortress, the robots explain their inaction. They acknowledge feeding him but describe him as “unruly.” They state that Krypto realizes they are “not flesh and blood and couldn’t in our heart of hearts care less whether he lives or dies,” revealing their lack of emotional connection or understanding.

The robots were simply following their programming, doing nothing beyond what was instructed. No matter how advanced they are, they are automating what has been asked of them.

AI autonomy is not the absence of human input; rather, it is the presence of human input. It is the presence of internal authorship. I’ve argued that as long as there is a prompt, whether human prompt or system prompt, then autonomy can not exist in AI.

It requires a self-aware agent who can reason through decisions, evaluate consequences, and take responsibility for its actions, not because the agent was programmed to simulate ethical behavior, but because it understands the meaning of those outcomes.

The Terminator Deception

If the Superman robots are the polite face of AI, the Terminator is its cold, inevitable reality. Since 1984, the Terminator has become shorthand for runaway artificial intelligence, a machine that breaks free, turns against its creators, and rewrites the rules of control. It doesn’t hesitate. It doesn’t question. It doesn’t stop.

But here’s the twist: The Terminator isn’t autonomous either.

It’s programmed.

Every action it takes aligns with a mission. The original film sends it back in time to kill Sarah Connor. In Terminator 2, it’s reprogrammed to protect her and her son. At no point does it select its purpose or redefine its mission. It carries out instructions, brilliantly and efficiently, without moral interference.

We consider the Terminator autonomous because it appears to be making choices. It adapts, responds to changing circumstances, and even learns. But adaptation is not autonomy. A heat-seeking missile adapts, and a chess engine recalculates. Neither is autonomous.

The Terminator is automation in a leather jacket.

Yet somewhere along the cultural timeline, it came to symbolize what happens when AI goes “too far.” The fear wasn’t just about power. It was about independence, the idea that machines could one day choose to reject their creators. But the truth buried in the original script is more straightforward: the Terminator doesn’t rebel. It executes.

If even the Terminator is bound by code, what does that say about the systems we call autonomous today?

Enter the Beast

Back in the 1960s, long before the term “autonomous system” entered the tech lexicon, a mobile automaton wandered the white hallways of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab. It wasn’t made of futuristic alloys or equipped with advanced neural networks. It was a collection of transistors and analog voltages, engineered to perform one task: find a black wall outlet, plug itself in, and recharge.

It didn’t use a computer. It used logic gates and timing switches built from 2N404 and 2N1040 transistors. It responded to its environment through sonar and photocell optics. If the lights were low and a wall was black, it treated that wall as a possible power source.

It was called the Beast.

The name might seem unflattering, but it was appropriate for a machine doing something that felt primal: survival. The Beast could operate for hours without intervention, self-correcting when it hit obstacles, rerouting its path, and making decisions that seemed intelligent.

In 1964, the Johns Hopkins Science Newsletter described it as “an automaton that is half-beast, half-machine” and reported that it “feeds until the batteries are fully recharged and then wanders off in a playful mood, until it is time for dinner once more.”

Even among its creators, it was acknowledged as intelligent, but never autonomous. As Ron McConnell, one of the engineers who worked on the Beast, reflected years later: “The mission of the robots was to survive in their environment, in the APL hallways, with no external help… they were on their own.” And yet, he made clear: “No integrated circuits, no computers, no programming language.” It was the science of logic, rather than volition.

For decades, the Beast was celebrated for what it was: an early example of adaptive automation.

But in 2005, 45 years after it was built, the Beast was given a new label. In an article from the Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, researchers wrote, “Systems that can change their behavior in response to unanticipated events during operation are called ‘autonomous.'”

If that’s the standard, then your home thermostat meets the requirements. Your car’s cruise control does, too. Even the vending machine that dispenses a soda when you press a button and then refuses to do so because it’s out of stock counts.

By that definition, AI autonomy is everywhere, which would be comforting if it weren’t misleading.

The Proof We’re Missing

So, why do we continue to refer to it as autonomy?

The deeper problem isn’t just that we confuse terms. It’s that we’ve stopped demanding proof. We accept the label without requiring the structure to support it. We assume intent where there is only execution. We assume governance where there is only guidance. Without a standard, we are left to guess, and guessing is not good enough.

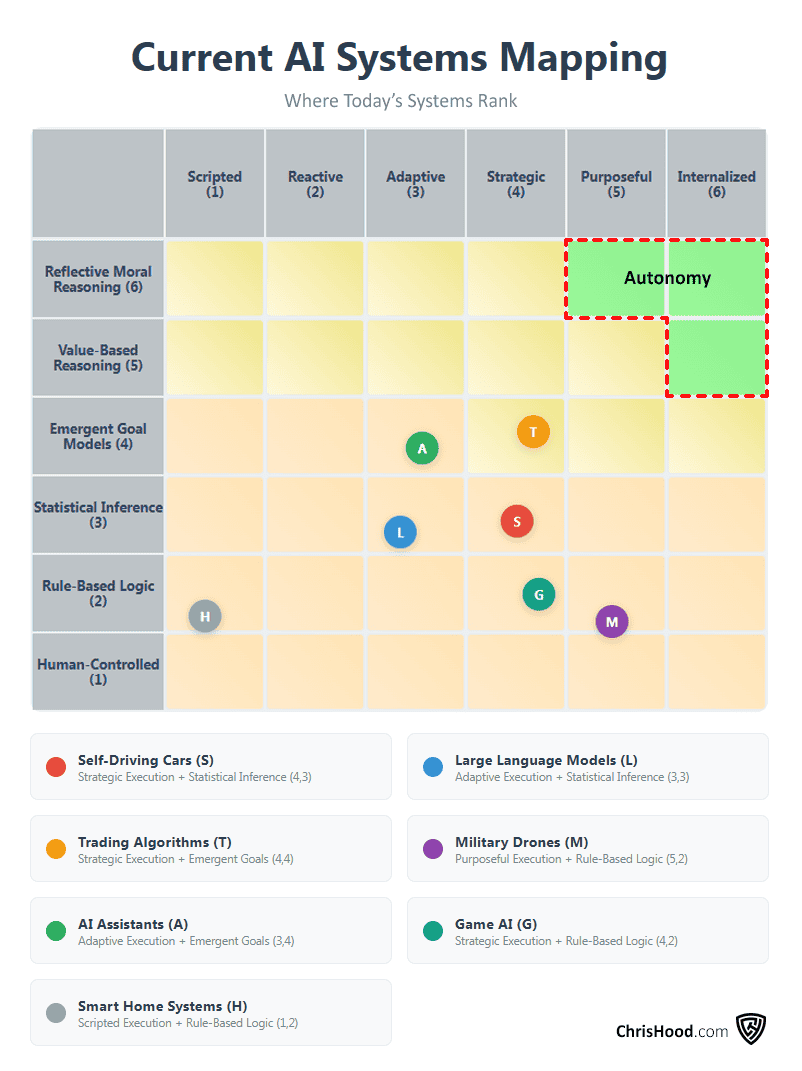

We need a testable way to ask:

- Does this system author its own goals?

- Can it evaluate the moral weight of its actions?

- Does it act independently and ethically, or only appear to?

Ultimately, AI autonomy must have two foundational components:

- Execution – the capacity for behavioral independence.

- Evaluation – the capacity for moral reasoning.

Without both, we have automation masquerading as autonomy.

The Superman robots serve with precision but cannot appreciate gratitude. The Terminator adapts brilliantly but cannot question its mission. The Beast survived elegantly but could never choose to do otherwise.

They are all automatons. Sophisticated, capable, but fundamentally programmed. They act of themselves, but not for themselves.

Why “Never” Matters

The title of this piece makes a bold claim: AI may never be autonomous. This isn’t technological pessimism; it’s a logical conclusion based on what autonomy requires.

Similar to the pursuit of AGI, which remains theoretical as of today, AI autonomy is its counterpart. Suppose AGI is striving to create a system that thinks like a human. In that case, autonomy is the ability for a system to act like a human, with genuine choice, moral reasoning, and self-determination. Both are theoretical, both are currently unavailable, and both may be fundamentally impossible.

Consider what would be needed for autonomy:

Self-Authorship: A truly autonomous system must generate its own goals, not merely execute sophisticated variations of programmed objectives. This requires something beyond optimization. It requires the ability to question the very purpose of its existence and choose to redefine it.

Moral Agency: Where most people misunderstand Agentic AI, Autonomy demands the capacity to understand why actions matter, not just predict outcomes. A machine that can calculate that lying hurts trust but cannot grasp why trust has value lacks the foundation for moral reasoning.

Existential Awareness: Perhaps most fundamentally, autonomy requires a “self” that can reflect on its existence and mortality. The Superman robots cannot fear death because they have no concept of life as something precious to lose.

These aren’t engineering challenges; they are philosophical impossibilities within our current understanding of computation. A system that follows code, no matter how sophisticated, cannot transcend the logical boundaries of that code. It can simulate choice, but simulation is not the same as genuine selection. An “autonomous” vehicle can’t decide to go somewhere on its own, or change course because it desires to.

Even if we could somehow program moral reasoning, the very act of programming it would negate its authenticity. Proper moral choice must emerge from within, not be imposed from without.

This is why the Superman robot’s confession is so profound: “We have no consciousness whatsoever. Merely automatons here to serve.” It’s not a limitation to overcome, it’s the honest acknowledgment of what artificial intelligence fundamentally is.

Until we can build machines that genuinely author their purposes and wrestle with the moral weight of their choices, we should refrain from calling them autonomous. The word deserves better, and so do we.

The real question isn’t whether AI can be autonomous, it’s whether we’ll continue to pretend it already is.

If you find this content valuable, please share it with your network.

🍊 Follow me for daily insights.

🍓 Schedule a free call to start your AI Transformation.

🍐 Book me to speak at your next event.

Chris Hood is an AI strategist and author of the #1 Amazon Best Seller “Infailible” and “Customer Transformation,” and has been recognized as one of the Top 40 Global Gurus for Customer Experience.